A primer on prioritization

![map[class:w-xl px-6 xl:px-12 resources:[images/nnln-model-example.png] src:images/nnln/now-next-later-never-model.png]](/images/nnln/now-next-later-never-model.png)

Anyone who has ever worked in technology has experienced the joy of having to decide how to spend their precious and limited resources on projects. What, though, is a rational model for deciding?

Random, Whim-based, or Interest-based

I put these strategies together because they’re effectively the same. Picking something and getting work done, whether that’s because it looks like a fun task, or because you liked the joke someone made in the description, or whatever.

The benefit of this approach is that it keeps developers working, and features do get shipped. It’s hard to argue that something shipped is better than nothing shipped.

But, is what has been delivered created the maximum value? What evidece is there that you made the optimal use of the development hours available? If you go to ask for more developer time, how do you rationalize your efforts?

The Value ✖️ Complexity Matrix

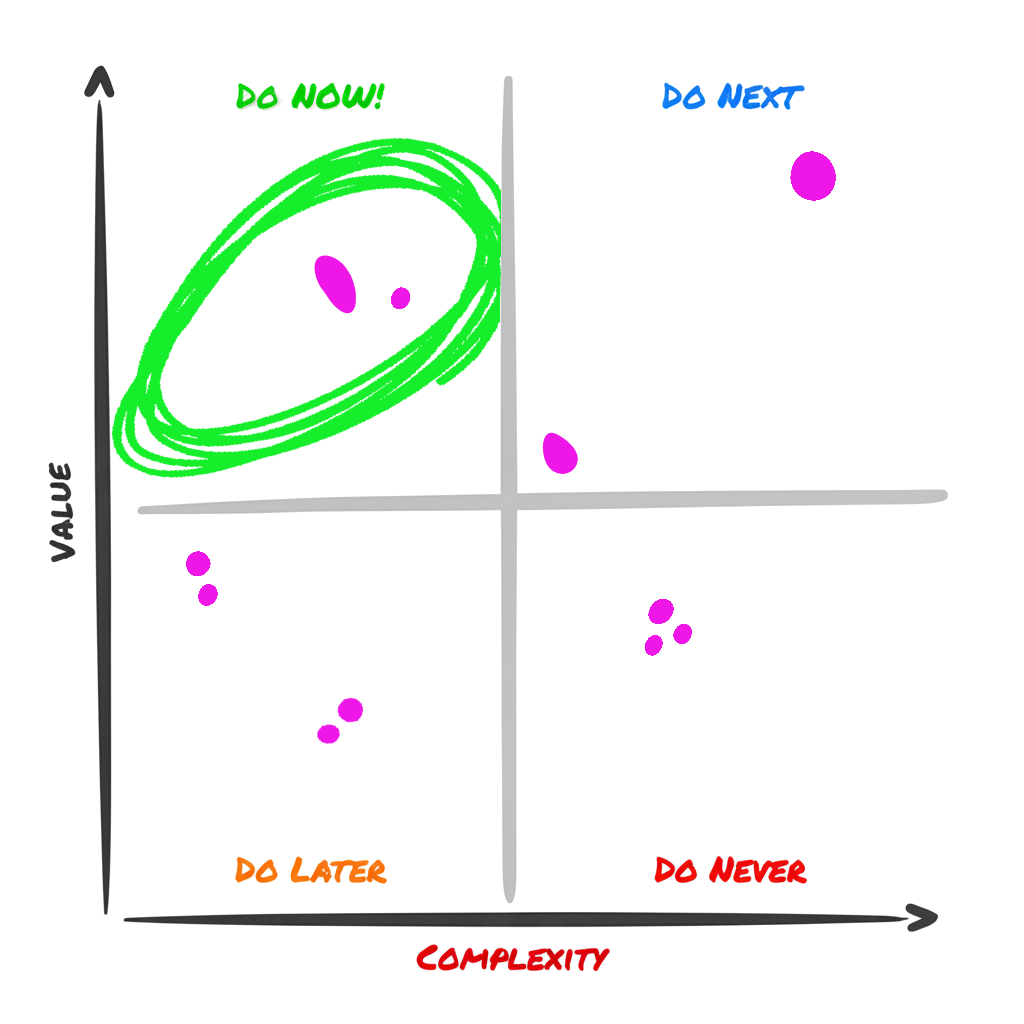

What if, instead, we mapped features on a Value and Complexity chart?

Imagine now you’ve got the following chart. Items along the top have higher value, and items further to the right have higher complexity. Now, it becomes simple to not just know what the immediate next items should be, but also what might be prioritized in following work units.

But, that raises the question of who is making those decisions, and with what information?

Like so much in tech, it all starts with a pile of sticky notes and a whiteboard.

Determining Value

The first step should sound familiar. Ask the product owners to rank the features listed on the notes by value for their users. With a one-owner product, this is a fairly straightforward exercise. In other cases with multiple product owners, it’s quite possible to have a contensious workshop. As a facilitator though it is important to let the process play out.

Once it’s done, you’ll have a good idea of what the relative value of each feature.

It is here where oftentimes the process stops. That’s not a terrible outcome, but further refinement will provide a clearer path forward.

Determining Complexity

Now, we bring in the technologists. The development team. The whole team. Let the team discuss the state of the system, the architecture tradeoffs, technical debt, but don’t let them leave until they’ve moved each of the stickey notes left or right to find a good spot in terms of complexity.

It often takes time for the team to come to consensus. It could take more than one session to complete the exercise. However, at the end, you’ll have a good roadmap and a good story.

All that’s left to do is implement.

Moving the Needle

There are times where the functional use cases don’t tell the whole story, where a strong architect or technical lead can see a few extra steps into the future. As a project owner, it’s important to take advantage of this.

The technical leadership must be given the chance to add nonfunctional technical tasks to the matrix. The instructions they are given are to identify tasks that can shift the relative complexity of some or all of the functional tasks to the left. Sometimes, the tasks will be to pay down technical debt and execute refactoring. Other times, it might be to introduce a new architectural component to ease some aspects of implemnetation. The techincal leaders are in the best position to provide advice on these aspects, the order and impact of the tasks.

This is the “force multiplier” effect. A well placed technical task can enable the rapid completion of functional tasks.

Never Stop

The universe isn’t static, and project roadmaps shouldn’t be either. The prioritization, complexity and technical enablement exercise needs to be re-evaluated periodically.

Product owners evolve their understanding of the market. Implementation complexity can increase or decrease with architectural changes, knowledge gathered or team composition.

Seeking Help?

Does your team need help facilitiating a periodic roadmap exercise? Request a Meeting